Tom Elliot was one of the first young men to graduate from Duntroon Military Academy. He sailed off to war with the second contingent in December 1914. Elliot fought at Gallipoli with the seventh light horse and was evacuated to Malta in September with severe enteritis. By June 1916, at just twenty-two years of age, Tom had achieved the rank of major. He was sent on to the Western front to join Pompey Elliott’s 15th Brigade.

On July 16, 1916 just before 6 o'clock in the evening, Tom Elliott led his men out of the trenches. It was a fine summer night and although the artillery barrage had scared the landscape, enough of a wheat crop remained to glow gold in the sunset. That night the wheat was cut down by concentrated fire from the German trenches. Men fell in what was called ‘grazing fire’, Tom Elliot amongst them.

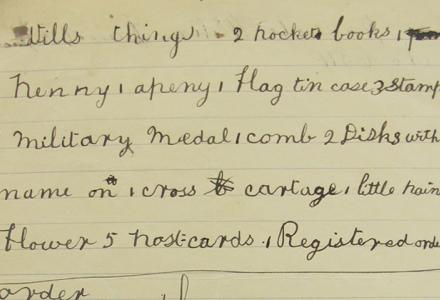

As with hundreds of men lost that night, Tom's body was never recovered. A comrade had seen him falling in the mud, a ‘big gash in his back’ and bleeding profusely. But no one had seen him killed, and so technically Tom was missing. In the carnage at Fromelles, there was very little hope of survival. His commander, Brigadier General Pompey Elliott wrote a long and intimate letter to Tom’s family. He offered what comfort he could.

But Mary Elliot refused to accept her son was dead. Accounts of the battle were confused and contradictory. And whatever did that awful word ‘missing’ really mean? It is ‘an awful thing’, she protested, to leave his mother in doubt. ‘If you know anything about him in mercy let me know… I can’t make anything of the war but that it is wrong, wrong, wrong, from beginning to end.’

Like thousands of others Mary Elliot questioned the sense of a war that ‘maimed’ of killed her children. She found no comfort in patriotic clichés—it was all just a ‘wretched slaughter’. Mary Elliot turned to drink, was given to violent outbursts and sent to Callan Park Mental Hospital. Discharged after inadequate treatment, her delusions mania and drinking only worsened. By November she had been admitted to Parramatta Mental Hospital. She died there in June 1919 of Spanish flu.

The war took everything from Mary Elliot, the boy she loved, her sanity, her purpose for living. In her time in the asylum she was troubled by recurrent visions of Tom returning. Mary’s other three sons suffered multiple wounds and Norman, Tom’s younger brother, died of tuberculosis at twenty-one years of age. Such was the damage the Great War inflicted on a single family.

The Memorial to the Missing at Fromelles honours the name of Major Tom Elliot. Every year, Australian pilgrims visit the site, speeches are made, flags raised in the air, flowers placed reverently on cold white stone. But few remember Mary Elliot, or the price she paid for that ‘rotten commercial war’.

For full attribution of sources, suggestions for further reading and an extended version of the story itself see ‘A Duntroon man: Tom Elliot’ in Bruce Scates, Rebecca Wheatley and Laura James, World War One: A History in 100 stories (Melbourne, Penguin/Viking, 2015) pp. 97-99; 356.