When Australia marched to war in 1914, and the world plunged into madness, Arthur Rae, unionist, Labor leader, feminist and socialist pleaded for peace.

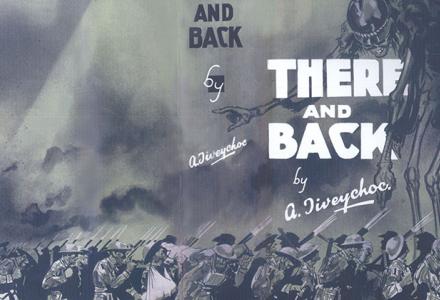

He believed a new nation should not fight for old empires; that war profited a few at the cost of the many; that the violence that tore Europe apart might have been avoided. In parliament, the pages of the press and stormy meetings of the peace movement, Arthur Rae spoke out against conscription—and was called a traitor; called for diplomacy—and was dubbed pro-German; faced ridicule, isolation and contempt.

Rae was unusual amongst Labor leaders in that he opposed Australia’s participation in the war from the outset. Most of his party rallied to the flag. It was a Labor Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher, who uttered that famous phrase vowing to support the Empire to the ‘last man and the last shilling’. Rae, by contrast, remained true to the internationalism that shaped his long career as a radical. It was Rae who helped commit the infant Labor Party to a socialist objective in 1896; twenty years later he moved the motion opposing conscription at the NSW state conference. At the 1918 Federal Labor Conference, Arthur Rae argued against the departure of further enforcements overseas. His motion to that effect was only narrowly defeated.

Rae hoped that by ‘the end of the twentieth century’ Australia would become ‘a free and independent Republic.’ ‘Every Empire’, he declared, ‘has been founded on force and fraud’, and it was Empire that drove the nation’s ‘heroic youth’ to slaughter in Europe.

Senator Arthur Rae may have opposed the Great War. But he also had three sons who served overseas. Two of them died, Billy in 1918, and Donald after the fighting had ended.

Private William Rae was first buried at Marcelcave, a battlefield cemetery near Amiens. After the war, the body was exhumed and taken to the Australian National Memorial at Villers-Bretonneux. It lies there to this day, on a gentle slope leading to a shining white tower, flanked by the names of the missing. And to this day a father’s words challenge the sense of war that swallowed up a generation.

Another Life Lost

Hearts Broken

For what?

Arthur Rae’s story reminds us that the Great War was one of the most divisive wars in our history. It tore families and communities apart. It also saw the birth of an anti-war movement many Australians have largely forgotten and a popular movement against the introduction of conscription. Most important of all perhaps, the epitaph chosen by Arthur Rae underscores the futility of 1914-18. Within Rae’s lifetime, the world marched to war again.

For full attribution of sources, suggestions for further reading and an extended version of the story itself see ‘Hearts broken for what?: Arthur Rae’ in Bruce Scates, Rebecca Wheatley and Laura James, World War One: A History in 100 stories (Melbourne, Penguin/Viking, 2015) pp. 149-150; 357.