In 1919, Tasman Millington married Ruth Martin. Together they travelled to Gallipoli and Tasman took up his post with the Imperial War Graves Commission. When Millington had fought there in 1915 the beach had been a place of death and suffering. Now, with his young wife and their baby boy Bernard ‘Anzac’, this became a place of life and renewal. His son would be baptised in the waters of Anzac Cove.

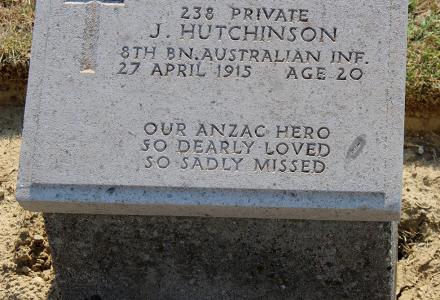

Millington and his wife would live in Turkey for over fifty years. At first they set up home in Kelia, literally bordering the battlefields. Millington would walk that lonely landscape almost every day. The bones of the dead were brought in from the gullies, reverently buried in purpose made graveyards, marked with tombstones shipped all the way from England. Millington took care to bury men as close as possible to where they fell. In that way, the landscape became their memorial: Quinn’s and Courtney’s, Baby 700, and the Nek battlefields were remade as graveyards.

Creating the cemeteries was hard work. An army of Greek stonemasons, exiled White Russians and Turkish peasants worked under Millington’s careful direction. They terraced the hillsides, shifted tons of earth, and hauled into place great blocks of freshly chiseled stone.

It was not until the early 1920s that this was a place fit for visitors. Even so, as soon as the war had ended the first pilgrims came. It fell to Millington and his wife to comfort these determined, if reluctant, travellers.

What came of Bernard ‘Anzac’? Like his father, Flight Sergeant Bernard ‘Anzac’ Millington also went to war, serving in the Royal Air Force. He survived both his father and his mother.

Tasman Millington died in England in 1962. He is buried, beside his wife, in Sidcup Cemetery, Kent, hundreds of miles from the graveyards he helped establish and eight thousand miles from home.