Born in Munbannar, Victoria, Sister Rachael Pratt was one of the first Australian nurses to enlist. She tended to the sick and wounded in Egypt, on Lemnos and in hospital ships within sight—and fire—of Gallipoli. Stationed in France in 1917, the casualty clearing station where she worked was bombed by German aircraft. Pratt was severely wounded in the attack but nursed her patients until she collapsed. Evacuated to England, a shard of shrapnel still in her body, Sister Pratt was presented to the King and awarded the Military Medal ‘for bravery under fire’.

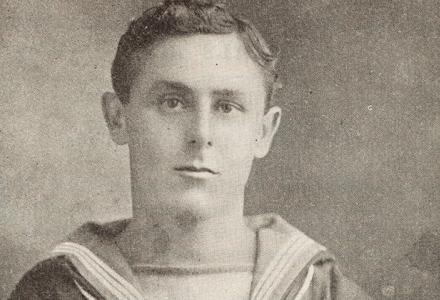

Pratt’s story is often told by those who manage the memory of Anzac. Keen to incorporate women in a heroic lexicon of war service, her portrait beams from commemorative websites commissioned by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Invariably the image is the same. Sister Pratt is dressed in her uniform, wearing her medal, she looks proudly towards the camera. Celebratory accounts of her life speak of courage, devotion and self-reliance.

Repatriation files paint a somewhat different picture. Pratt was admitted to Berklea Private Hospital for the mentally ill in 1938 suffering from what was vaguely termed ‘war neurosis’. Initial assessments of her condition were dire: ‘depressed and melancholic’, one doctor wrote, ‘worried the whole of her waking hours’. Another noted their patient was ‘unable to face anything’. Despite earlier success in private nursing after her return from the war, Rachael Pratt ‘had lost all self-confidence … has no companionship … and no practical purpose in life’.

Transferred to Merton Private Hospital, Pratt’s ‘mental outlook’ worsened. ‘[No] improvement whatever’, a Dr Godfrey noted, ‘[she] requires careful vigilance as she is suicidal … Last week she secured a pair of nail-scissors, and hid them in her clothes. They were missed … on her being searched, she transferred them to her vagina. She then admitted her intention was to open a vein in her wrist’.

At Merton, Pratt was treated by ‘modern methods.’ In August 1939 doctors began a course of Cardizol injections, a circulatory and respiratory stimulant. Doses were high enough to send her body into seizures. When convulsive therapy failed the doctors administered Somnifaine ‘at such a frequency as to maintain a condition of narcosis for three to four weeks.’ That treatment also failed. Sister Pratt died in the Heidelberg Repatriation Hospital in 1954. Hers was a long and ‘awful’ war.

Rachael Pratt’s story reminds us of the way that remembering war can sometimes be a form of forgetting. Those who speak with pride of wartime sacrifice and service conceal or overlook the sordid reality of post war lives. Thousands of veterans, Pratt amongst them, never recovered from their injuries. Their post-war story is a much harder one to tell.

For full attribution of sources, suggestions for further reading and an extended version of the story itself see ‘Her war never really ended: Rachael Pratt’ in Bruce Scates, Rebecca Wheatley and Laura James, World War One: A History in 100 Stories (Melbourne, Penguin/Viking, 2015) pp. 257-259; 361.