Stories

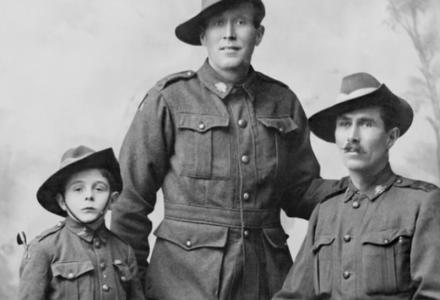

Garry Roberts’ son was killed at Mont St Quentin in September 1918. His first response was confusion, disbelief, and denial. And compounding the tragedy was that the war itself was so close to ending. Frank Roberts was killed in one of the last great battles Australian forces would fight.

Telling his wife Berta of Frank’s death was heartbreaking. As was breaking the news to Frank’s young widow Ruby. Ruby was distraught that her ‘little Nancy [would] never see her father’. Frank Roberts had sailed for war within weeks of Ruby falling pregnant—he would never hold his baby daughter. Nor would one of Nancy’s tiny booties reach her proud father. That parcel—sent by Ruby—was returned to the Roberts family, the cold word ‘DECEASED’ scrawled across it.

Garry Roberts’ life didn’t end with the death of his son. But what began was the business of remembering. Garry began ‘Frank’s Memorial Book’ on his 58th birthday. It swelled with cuttings from papers and obituaries, extracts from patriotic poems, handwritten notes of sympathy—all read and re-read time and time again.

At the end of the war, the Second Division raised their own memorial in France. It was placed on the summit of Mont St Quentin where Frank and over four hundred other Australian soldiers had been killed. Unlike every other divisional memorial, this one took shape of an Australian soldier bayoneting a German eagle. And at Roberts’ insistence, the face of that soldier was based on that of his son. In 1940, the German Army marched again through Mont St Quentin. The Second Division’s digger was one of the few war memorials they destroyed.

But Frank’s memorial books survived—as did that pair of baby’s booties. Sometimes the most fragile and private memorials prove more enduring than monuments cast in bronze.

Frank Roberts’ story provides a rare opportunity to revisit the private moment of grief and loss. The poignant intimacy of his narrative underscores how individual, variable, and personalised the process of mourning truly is. It suggests myriad ways loved ones were memorialised and shifts our attention away from public monuments to the intimate spaces of family and home. It also alerts us to the gendered dimension of remembrance; stoic masculinity grappling with the corrosive properties of grief.